Cobalt Mining in the Congo

Cobalt Mining in the Congo

In the vibrant dance of technological progress, cobalt has taken center stage — a star of modernity, illuminating our world with its indispensable presence. It is cobalt that gives life to our smartphones, to the electric vehicles that promise a greener future, and to the renewable energy that fuels our hope. Yet, as we marvel at the fruits of innovation, there lies a hidden sorrow — a profound human cost that remains shrouded in the shadows.

In an era defined by technological advancement, cobalt has become a critical component in powering our daily lives. From smartphones and laptops to electric vehicles and renewable energy, cobalt’s unique properties are indispensable. However, beneath the shiny veneer of modern innovation lies a dark reality: the exploitation and suffering associated with cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). While cobalt is undeniably valuable, the unethical practices that plague its extraction demand immediate attention and reform. But what are the true costs of cobalt’s prominence?

The book “Cobalt Red” by Siddharth Kara, an American author and activist, echoes the hidden tragedy of our technological progress. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), a country riddled with conflict and a legacy of geopolitical struggle for resources, holds nearly half of the world’s cobalt reserves. Within the DRC’s mining sector, human rights abuses and child labor abound. As Kara’s investigation reveals, despite pledges of reform by companies like Apple and Samsung, the insatiable demand for cobalt has only intensified.

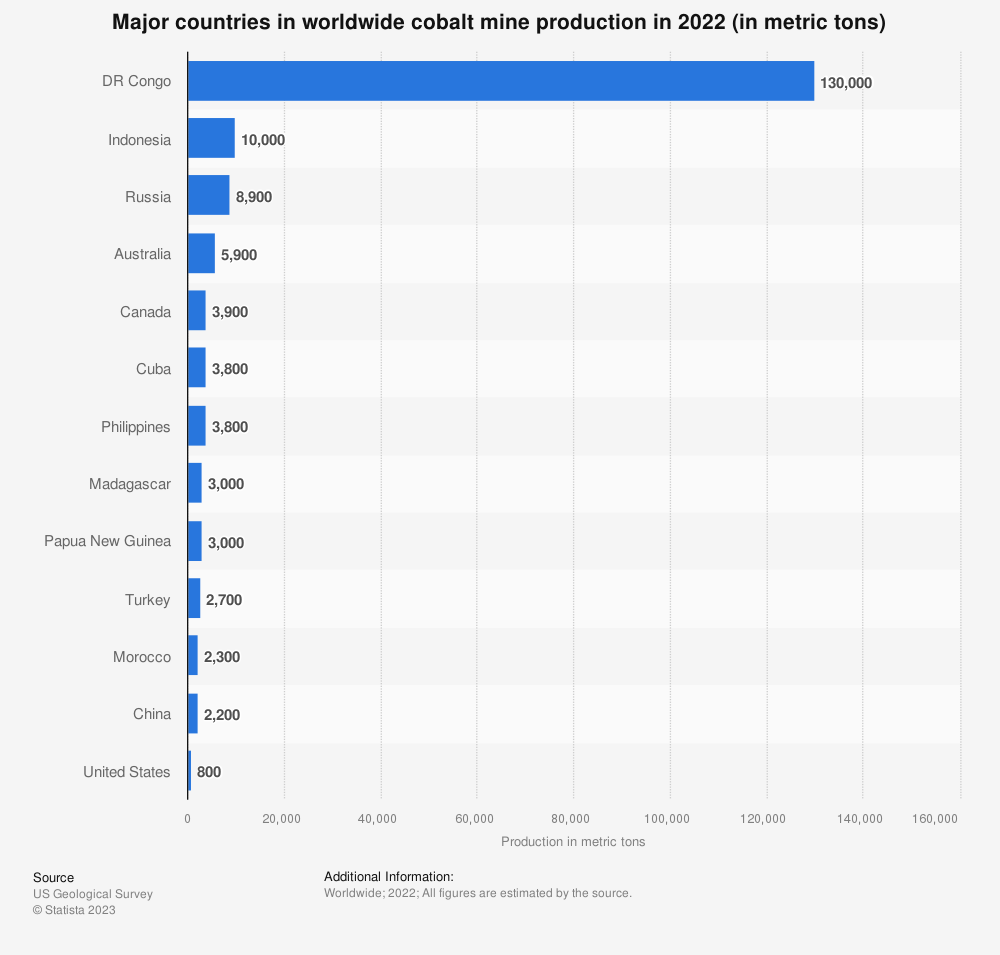

Source: Statista

Source: Statista

As Kara explains, the DRC has long been a supplier of riches to the world, from ivory and rubber to diamonds and uranium. Yet, despite its mineral wealth, the majority of the Congolese population lives in poverty, with little access to basic necessities like clean water and electricity. The mines have left a legacy of impoverishment rather than prosperity. Mining towns, constructed by the Belgian colonial monopoly, drew labor from far and wide. The rise of kleptocracy under Mobutu Sese Seko and the collapse of state-owned enterprises like Gécamines led to a shift to precarious, informal mining.

Against the backdrop of geopolitical tensions, including the U.S. conflict with China, Congolese politics and mining concessions remain a contested terrain. Chinese companies, dominating the electric battery industry, produce a significant portion of the world’s refined cobalt, with a portion excavated and processed by artisanal miners. Cobalt deposits often lie close to the surface, enabling extraction with simple tools. However, the conditions under which miners labor are treacherous, with the ever-present risk of accidents and toxic exposure.

Kara’s journey through Congo’s mining provinces uncovers the harsh realities faced by miners who toil in open pits and tunnels. In places like the Shabara mine, thousands of miners labor with little room to move or breathe. The absence of protective gear and the presence of armed guards exacerbate the hazards. As Kara bears witness to accidents, injuries, and fatalities, the human cost of cobalt mining becomes strikingly apparent.

Source: NPR

Source: NPR

The exploitation of cobalt is not limited to the mines; it extends throughout the supply chain. Artisanal cobalt is bought by traders, passed through checkpoints and bribes, and sold to processing facilities, where it blends indistinguishably with industrially mined cobalt. Regulatory circumvention and corruption are rampant. Attempts at transparency and traceability falter, revealing the challenges of ensuring a clean supply chain for cobalt. This opaque and convoluted process facilitates a lack of accountability at each stage of the supply chain.

As artisanal cobalt makes its way through checkpoints, depots, and processing facilities, it becomes nearly impossible to trace its origin and the conditions under which it was mined. While some companies may claim to implement transparency and traceability measures, the sheer complexity of the supply chain, coupled with rampant corruption, undermines such efforts. The absence of robust oversight mechanisms allows unscrupulous actors to capitalize on regulatory loopholes and ethical blind spots, as highlighted in Amnesty International’s report, “This is What We Die For: Human Rights Abuses in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Power the Global Trade in Cobalt.”

The plight of these child miners in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is a glaring example of how the pursuit of valuable minerals can lead to systemic human rights abuses. As they labor in the mines, these children face numerous hazards, including exposure to toxic substances, the risk of tunnel collapses, and physical injuries. The detrimental effects extend beyond their physical well-being; their psychological and social development is also at stake as they are deprived of the opportunity to receive an education and enjoy a normal childhood, as documented in Amnesty International’s report.

Both Kara’s book and the Amnesty International report underscore the moral imperative of ensuring that the quest for valuable minerals does not come at the cost of human dignity and fundamental rights. Together, they provide a compelling and urgent case for the need to reform and regulate the cobalt supply chain. By examining the human cost and shining a light on the troubling conditions of cobalt mining, they serve as catalysts for change — inspiring stakeholders to take action and advocate for a future where the technological progress powered by cobalt is harmonized with ethical sourcing and social justice.

As I read Kara’s book and the Amnesty report, through Kara’s vivid descriptions and Amnesty’s meticulous research, I bore witness to the toils and struggles of individuals who faced unimaginable conditions as they mined for a mineral deemed indispensable by modern society.

The weight of their plight struck me deeply. In particular, I was moved by the account of a young miner named Kasulo, whose dreams of becoming a teacher were dashed by the harsh reality of cobalt mining. She spoke of days spent in dark tunnels, where the air was thick with dust and the echoes of hammers reverberated through the earth. Her voice, both haunting and resilient, revealed the human cost of a mineral that so seamlessly found its way into the devices I used daily.

The book stirred within me a profound sense of introspection, and I began to contemplate the concept of the mystification of production. As a society, we often find ourselves enamored by the sleek designs and innovative features of our technological devices. Yet, how seldom do we consider the journey of their creation? How rarely do we pause to think about the hands that extracted the minerals and the lives that were affected in the process?

This mystification, a form of technology fetishism, obscures the true nature of production and creates a detachment between consumers and the ethical implications of their choices. It is all too easy to become entranced by the latest gadgets and advancements, but in doing so, we risk losing sight of the human stories behind them.

Kara’s “Cobalt Red” challenged me to confront this detachment, to question the moral dilemmas of our interconnected world, and to recognize the importance of ethical consumption. It implored me to see beyond the surface and seek a deeper understanding of the impact of my choices.

I found myself grappling with the consequences of technology fetishism — a phenomenon that inadvertently perpetuates exploitation and erodes our sense of empathy. I realized that to break free from this mystification, we must actively engage with the narratives of those who are affected by production and amplify their voices in the discourse on technology and ethics.

As I closed the book, I was left with a sense of resolve — to be an advocate for change, to embrace a conscious approach to technology, and to honor the dignity of all individuals in the pursuit of progress. Siddharth Kara’s “Cobalt Red” had kindled within me a desire to contribute to a world where technological marvels and humanity exist in harmonious coexistence.

Let us raise our voices in unison, urging accountability and justice in the cobalt supply chain. Let us challenge the systems of exploitation and inequality that perpetuate suffering. Let us embrace innovation that seeks alternatives and alleviates dependency. Together, we can illuminate a path that reconciles the brilliance of technology with the radiance of compassion.

Source: Future Hope Africa

Source: Future Hope Africa

References

-

US Geological Survey. “Major Countries in Worldwide Cobalt Mine Production in 2022 (in Metric Tons).” Statista, Statista Inc., 31 Jan 2023, https://www-statista-com.proxy.library.nyu.edu/statistics/264928/cobalt-mine-production-by-country/

-

Amnesty International. “This is What We Die For: Human Rights Abuses in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Power the Global Trade in Cobalt.” Amnesty International Ltd, 2016, https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/AFR6231832016ENGLISH.PDF.

-

Kara, Siddharth. Cobalt Red: The Blood of Congo That Powers Your Cell Phone. Hot Books, 2023.